I'm just starting to dive deeper into educational theory, so much of what I'll be posting will be from my limited point-of-view. On first glance, there seems to be dozens or hundreds of different educational theories or systems in the literature. A large percentage of these seem to have very little in terms of independent validation.

With regards to teaching a new skill, the following elements seem to be widely accepted:

- Explain

- Demonstrate

- Practice

- Assessment

- Feedback

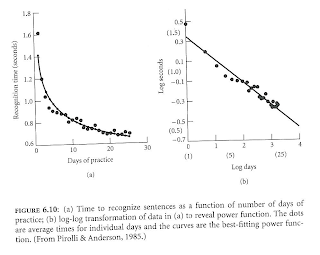

Power Law of Learning

I first learned of the power law of learning when I was taking Dr. John Anderson's cognitive psychology class at Carnegie Mellon University. Also called the power law of practice, this law states that memory performance improves as a power function of practice and is one of the most validated findings in education. Basically, the more you practice, the better you get and this improvement follows a logrithmic power curve -- faster improvement at the beginning followed by slower improvement as you reach peak performance. This curve is one of the origins of the term, "learning curve." The following graph from Dr. Anderson's cognitive psychology textbook demonstrates this effect.

The 10,000 Hour Rule

The next reference comes from a very popular recent book called Outliers by Malcom Gladwell. In this book, Gladwell researches and interviews successful people on the extreme outer edge of what is statistically possible and tries to determine how they got there. He finds that in almost all cases it is an accumulation over time of high-quality practice and repetition. Read the wikipedia review of Outliers for a more complete description.

Sports

Not only is this effect true in academics and business skills, but it also applies to sports and physical skills. Gladwell's book documents the case for Canadian youth hockey. Similarly, I remember an article about Russian youth tennis camps based on the same premise (but I can't find it right now). Coaching Youth Soccer by John McCarthy has this nice little nugget, "The more you get your players drilling their skills, within reason, the better your team will be. That's the surest thing about any sport."

3 comments:

I can't argue with the thesis of practice. Design ed & Computer Science programs seem to know this much better than other fields like social sciences. My time at CMU made me aware of two kinds of knowledge, procedural and declarative. Practice seems to promote the procedural which gets at actually doing something where as declarative is more intellectual and allows a person to explain something. It is often the case that someone can do something well but can't explain it.

These two kinds of knowledge are not really independent. They often work together to make a person more able. An example of what I'm getting at is a couple of experiences I've had with sports. In tennis, I struggled with my forehand for years. Prior to children, I would play or practice 3 to 4 times a week. But, the forehand didn't get better which I found very frustrating. Then when I had kids, I couldn't play much. I would still handle my racket and I did a lot of thinking about my forehand. I analyzed what I was doing and thought about what I needed to do. I looked at some instructions for the proper technique. These activities were much more about declarative knowledge than procedural. Then in the following years, I began to play a bit more and I put my ideas to practice and my forehand has improved dramatically. It is now my most effective shot.

My other example is in hockey. As a child, the coaches had us do drills. One of which had the defensemen move backward, away from their offensive end and pass the puck behind the net. As a child, it didn't make much sense to me and I couldn't see the value and I didn't learn much form those practices. I began playing hockey again as an adult and I gave some of those ideas some thought and the value was much clearer. I tried using those techniques and had quite a bit of success.

I guess the message is practice smart works a lot better than practice hard. The equation of more practice makes the person better isn't always true. The quality of the practice is an important variable in the equation.

I thought I might get these books by Malcom Gladwell on audio book. The local library has a huge back log. Must be quite popular. Funny, I didn't have much trouble getting books on Atheism.

John Anderson's theory is pretty close to the folksy 80/20 rule.

Post a Comment